By Josemaría Moreno

In these weeks we have seen how the country is trying to rescue its democracy. On the one hand, it was judicially confirmed that the Calderón government was a narco-state, and on the other, a significant block of the population came out to march in defense of the privileges of the bureaucracy of the INE, confusing propaganda with defense of democracy, as Bernardo Moreno points out in his column printed in this same issue of Atención.

For this reason, for this delivery of the essentials, full of dissatisfaction and pessimism, we propose to give a twist to the concept of anarchy. Rather than crudely defining it as a lack of principle, we see it as a fundamental principle of political and personal autonomy beyond the vices or virtues of any representative government. If a democracy by nature is incapable of governing for all, the individual may nonetheless flourish as a social being who does not identify with his political representatives. Even more, in a place like Mexico, where the government, with its thousand bureaucratic tentacles, seems to be an institution explicitly designed to seek inefficiency, anarchy is not just another political bet, but rather a necessary constant. In practical terms, one must live as if there were no government and the actions of each one was regulated by the consequences they manifest. That is, anarchy is a way of life. For this installment, we leave you three examples that address this proposal.

Epicurus, Carlos Garcia Gual (2013)

This excellent study of the celebrated Spanish Hellenist compiles all the known texts of Epicurus—adding invaluable footnotes as commentary and context that history has bequeathed to us, which, in the case of Epicurus, is more than haphazard. Since ancient times, Epicurus’ thought ran the risk of being lost, through being an odd bird among much more powerful currents—Platonism, Aristotelianism, Stoicism, to mention just three giants. However, Epicureanism was fortunate to have Lucretius as one of its greatest Latin adherents. The creator of De rerum natura breathed life into Epicureanism in order to survive an unrelated medieval Christianity. The concept that we are most interested in highlighting now is that of ataraxia, a lack of disturbance, both bodily and spiritual.

It is well known that Epicurus’ philosophy sought happiness, the good life, and, to achieve it, he recommended that his followers not interfere in the political gossip of their times or in the myths of their ancestors, but rather to nourish the spirit and find the peace that no one else but oneself can procure. Although Epicurus’ philosophy ended up becoming irremediably mixed with hedonism—the search for pleasure to avoid pain—his doctrine was not individualistic: Epicurus clearly recognized that any excess, especially that of unbridled pleasure, is a source of bitterness and sorrow, but, faced with gargantuan powers and institutions, the individual would do better to step aside, seek encounters of joy that spread joy to others, and dedicate himself, ultimately, to cultivating his garden, as Voltaire’s Candide would say with some pessimism but resolution.

Trainspotting, Danny Boyle (1996)

This extremely famous feature film marked the youth of the ‘90s, as perhaps no other film did, and it is still a cult film today. The premise will be easily recognized: a group of young junkies in Scotland do everything they can, destroying whoever stands in front of them, in order to get the next shot. The speech and summary of the film—pessimistic, intriguing, and captivating, which does not represent an apology, but rather the spiritual wear and tear that has marked youth for decades now—is taken by Renton (Ewan McGregor): “Choose life. Pick a job. Pick a career. Pick a family. Choose a fucking huge television, choose washing machines, cars, and electric can openers … Choose housework while wondering who the fuck you are on a Sunday morning … Choose to rot at the end of it all; nothing but a shame to the selfish brats you spawned to replace you. Choose your future. Choose life. But why would you want to do that? I choose not to choose life. I choose something different. And the reasons? There are no reasons. Who needs reason when you have heroin?»

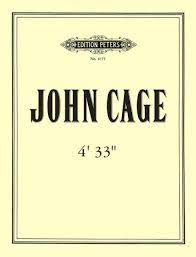

4´33”, John Cage (1952)

This controversial piece of music takes us to the antipodes of the previous recommendation. It’s an almost zen-like meditation and an absolute refusal to be determined even by something as basic as sheet music. It is chaos and spontaneous determination—an experiment designed to be interpreted by any instrument whose purpose is to contemplate the bustle and nonsense of existence, because although the score indicates that the musicians must remain silent during the duration of the piece (four minutes 33 seconds), all kinds of accidental noises and sounds are discovered in his interpretation: the interpreter’s breathing, his heart beats, the people stirring in their seats, the wind and the raindrops crashing against the windows of the venue. The sound of silence is an undeniable sign of the resistance that all existence manifests when faced with an external force that tries to determine it.