By Josemaría Moreno and Rodrigo Díaz

We celebrate Father’s Day on June 18. The origin of this holiday dates back to the US at the beginning of the 20th century, when William Jackson Smart, a survivor of the Civil War, was left to care for his family after his wife died giving birth to their sixth child. His daughter, Sonora Smart Dodd, in homage to her father, commemorated the work of all fathers in their small town near Washington, DC. The anniversary caught on, and by the 1960s became official. William’s case, though, was an exception.

Even today, raising a family falls mainly on the mothers or women of the family: according to INEGI (National Institute of Statistical and Geographical Information), in Mexico a father is absent in four out of 10 households. Further, 53% of Mexicans report having grown up with an absentee father or one who was seldom present due to work issues.

It is necessary to rethink paternity to achieve gender equality. Domestic and child-rearing work largely depends on women, and their work is generally unpaid, an important cause of the lag in wage equity between genders and a reason for women’s deficiencies or difficulties in the labor market.

Let’s celebrate our fathers responsibly with these three reflections on fatherhood.

“Reinventing Love,” Mona Chollet, 2022

The French author, one of the most recognized voices of feminism, gives us a means of reevaluating models of love today. It goes without saying that any model of paternity has to go through an intense reassessment and criticism of the daily forms that couple relationships take in a patriarchal context. The author fully dismantles the romantic myth on which most heteronormative expectations are based: love is violent, excessive, adventurous and, in for men, also the ideal way to manifest their true nature—troubled and dominant.

Not so for women, who turn out to be more of an accessory to bolster the masculine ego, which, not infrequently, decorates itself with dead female bodies.

Nothing could be further from the inventive and creative ideal that Chollet advocates. Even if patriarchy has modeled our most secret fantasies and our way of relating, that is not why we lack the tools to disrupt these models and make them work in our favor and in pursuit of a full and fulfilled agency in which women do not have to limit themselves to being a mere object. The magic formula is simple, but the obstacles remain monumental.

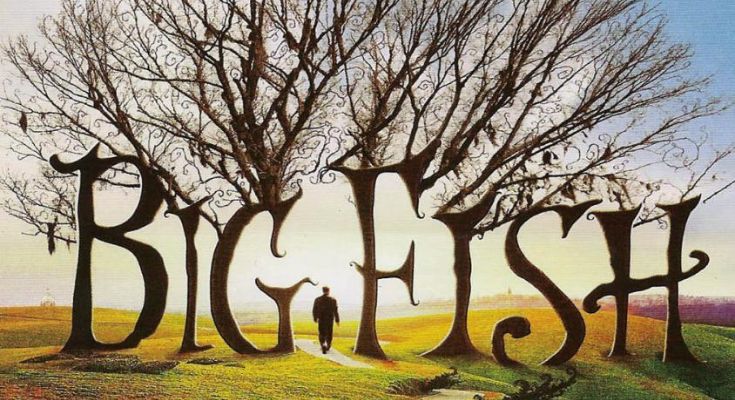

The Big Fish, directed by Tim Burton, 2003

This film, based on the book of the same name by Daniel Wallace, is loaded with symbolism and metaphors. We enter into the fantastic stories of Edward Bloom, a charismatic and determined man who lives great adventures. But then we meet reality: he is already old and, having been afflicted by disease, is on the verge of death. The plot centers on the conflict between Edward and his son Will, who does not believe in the fantastic stories that color his father’s life. The film oscillates between reality and fiction. As opposed to the dark and gothic landscapes to which he has accustomed us, this time Tim Burton presents us with bright and vivid colors that exalt the fictions in Edward’s life. The tone of the story changes, and the fantastic parts seem to describe a children’s story. Returning to reality, everything becomes serious and sad. In the end, without giving the plot away, Edward’s fiction was not so far from reality: the conflict here, between the lines, is the confusing communication between generations and the use of fantasy to avoid assuming reality as it is, something very common among fathers and sons.

“Amor Amarillo,” by Gustavo Cerati, 1993

This is the first solo release by the great Argentine musician, Spanish-speaking rock icon, and leader of the legendary band Soda Stereo, which released its sixth album, «Dynamo,» in 1992. After an exhaustive promotional tour, the members took time out for their personal lives. Gustavo Cerati got married to Chilean model Cecilia Amenábar, and they settled in Santiago de Chile. Rumors about the band’s break-up were spreading, following the public’s lukewarm reception of “Dynamo,” perhaps due to the band’s approach to shoegazing and house, genres that were still alien to Latin America in the early 1990s.

The atmosphere of uncertainty and his wife’s pregnancy inspired Cerati to explore sound paths that he had not been able to before, resulting in a “intimate” solo album, as the composer himself confessed, with an emotional sound that reflected the happiness of his new life with his partner and his wife’s pregnancy of their firstborn. “Amor Amarillo” navigates smoothly through 11 tracks full of subtle electronic sounds and sweet acoustic guitars—an unforgettable album.