By Janet Blaser

I set out confidently, list in hand, to get what I needed for a Champagne brunch I was hosting on the weekend. Ingredients for dishes I would prepare, both savory and sweet; a salad (hello farmers’ market!); fresh-squeezed OJ for mimosas; and, of course, Champagne.

But which Champagne? Confronted with bottles from France, the U.S., Mexico and Spain, plus Italian prosecco, I was pretty lost. Did more money necessarily mean better quality? Is prosecco the same as Champagne? What about Spanish cava and Mexican espumosos, from Baja’s Valle de Guadalupe?

I retreated home to my computer — sans Champagne — to figure out what was what. I knew the name Champagne can only refer to sparkling wine produced in a certain part of France, safeguarded by an AOC (Appellation Originale Contractualisée) or Designation of Origin.

It’s an age-old process that’s carefully protected and controlled; the first regulations were established in 1887, but Champagne as we know it has been documented since the early 1500s. Champagne must be labeled with the AOC mark, the name and address of the producer and the town or village where it’s from.

This protected beverage must be made utilizing the méthode Champenoise, a vinification process invented in the northeastern French province of Champagne, about 100 miles east of Paris. Distinguished by a secondary fermentation in the bottle — rather than barrels or tanks — and a double inoculation of yeast, Champagne must use a blend of pinot noir, pinot meunier and Chardonnay grapes grown in that province.

Utilizing those three base wines, each vineyard has its own closely guarded formulas and signature blends, or cuvees, drawing on hundreds of specific grape varietals. Like any other wine, the terroir (how much sun, moisture, temperatures, etc.) influences the taste and flavor profile of the grapes and the finished beverage.

Champagnes are aged a minimum of 15 months; the longer the aging, the more flavorful and aromatic it will be. The distinctive metal casing over the large, secure cork traps the fermentation caused by carbon dioxide being produced — what creates those famous bubbles.

Folklore has it that after inventing Champagne, Dom Pérignon invited his fellow friars to taste the new beverage by exclaiming, “Come quickly, I am tasting the stars!”

After bottling, Champagne is aged in the chilly air of hundreds of miles of underground caverns and tunnels built into the chalk hills beneath the fabled vineyards and towns of the area, which also served as bomb shelters during the German attacks of WWI. Official estimates say that at any given time, there are 200 million bottles aging below ground, mostly around the historic cities of Reims and Epernay. UNESCO declared the houses, cellars and hillsides of Champagne a World Heritage Site in 2015.

All of this is fascinating, but I still didn’t know which Champagne to buy for my brunch.

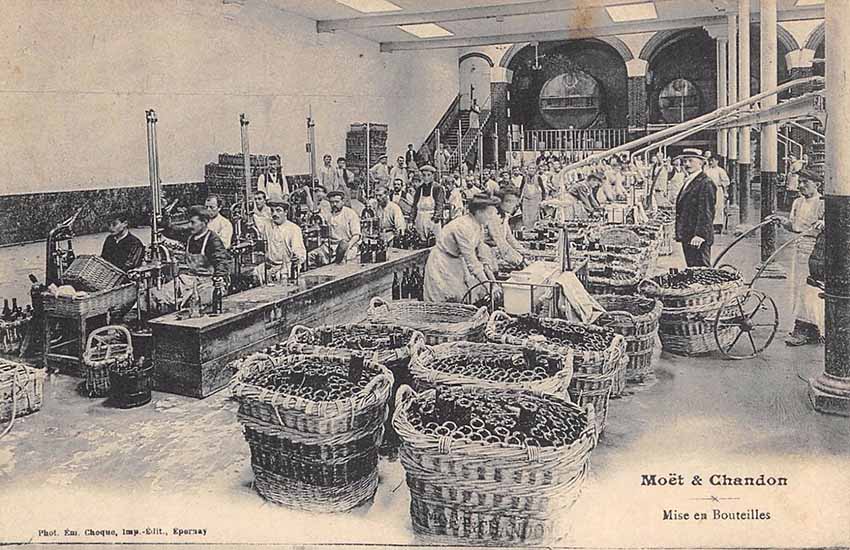

Like most things, you get what you pay for. Long-time producers — Ruinart, Taittinger, Veuve Clicquot and Moët & Chandon, all founded in the 1700s — have the most experience and thus produce better Champagnes. The oldest still in operation is Gosset, since 1584.

Within those brands are many categories and sub-brands, so read labels carefully.

Buy the best you can afford — and then taste conscientiously. Consider doing your own side-by-side tasting, with a few brands and a prosecco or two for good measure.

Champagnes have varying degrees of sweetness; if it’s labeled “brut” (which means “dry, raw, unrefined”) it has less than 15 grams of added sugar per liter; “extra brut” and “brut zéro” will be even drier. Ready to be confused? Champagnes labeled “extra-dry” or “extra-sec” have more sugar — lots more sugar — than bruts.

Experts advise against adding orange juice or anything else to Champagne; if you’re going to do that, they say, use a less expensive sparkling wine. (Oops.) You want the full Champagne experience — which means unadulterated, chilled well and served in tall flutes that keep the bubbles in as long as possible and allow the velvety fragrance to be released slowly and seductively.

Frequently asked questions:

Are Champagne and sparkling wine the same?

Champagne is sparkling wine — but not all sparkling wine is Champagne. Italian prosecco, Spanish cava and Mexican espumosos and Freixenet (a Spanish brand that also has vineyards and a winery in Querétaro under the name Freixenet México) are some of the many sparkling wines produced in countries other than France.

While not the same sophisticated flavor profile or complex hands-on production process as authentic Champagne, they’re delicious nonetheless, and the cost is more digestible: US $15–$20 for prosecco vs. US $40 and up for Champagne.

So what should I buy?

If you want real Champagne, do some research and then buy the best you can afford, considering also the level of dryness or sweetness. The older, popular and reputable French Champagne houses offer a variety of different price points as well as varying degrees of sweetness, flavor, aging and vintage or non-vintage years.

Costco in Mexico carries Veuve Clicquot, a respected French brand; a high-end example would be Moët & Chandon’s premium Dom Pérignon, a vintage Champagne produced only during good to excellent years.

What’s the fastest way to chill Champagne?

Don’t chill it in the freezer; the sudden temperature change can dull the flavor, and those sparkly bubbles too. If possible, refrigerate Champagne at least three hours before serving.

In a hurry? Use the classic bucket-of-ice-water method; adding a little salt to the ice water will further accelerate the chilling process.

How should I open Champagne?

That distinctive and explosive cork-popping is not the best way (although it may be the most fun!) You lose lots of the precious bubbles, which are a good part of the reason you’re drinking Champagne to begin with.

Instead, first remove the foil and wire piece. (If the bottle is wet, wrap a towel around it.) Then simply twist the cork gently but firmly until it opens. Voila!

Can you store an opened bottle of Champagne?

Rumor has it that dropping a raisin into an open bottle of Champagne (or any sparkling wine) just before drinking will revive its effervescence. Why? The raisin acts like a carbon dioxide magnifier, creating more bubbles with what’s left in the bottle. This only works for a few minutes, so drink up!

Janet Blaser is the author of the best-selling book, Why We Left: An Anthology of American Women Expats, featured on CNBC and MarketWatch. She has lived in Mexico since 2006. You can find her on Facebook.

*This excerpt was published with authorization. To keep reading please search for the link to Mexico News Daily: