By Kathleen Bohné

Below you will find an excerpt from the July 31 edition of “La Semana” newsletter. To read more and subscribe, please visit www.themexpatriate.com

“Facing the public is a sign of openness, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that citizen requests are honored…I think they are confusing the communicativeness of the government—the daily press conferences—with access to information.” In an interview last week, Eduardo Bohórquez (director of Transparencia Mexicana) assessed the current administration’s track record on access to information, in light of the crash of CompraNet, the electronic system for government expenditures that has operated continuously since 1996. Until July 15, 2022.

“We hereby inform that due to reasons beyond the control of this agency and the management of the CompraNet platform, starting at 16:00 hours on Friday, July 15 2022, there were technical errors in the infrastructure that hosts said platform, limiting its operations. For the aforementioned reasons, CompraNet is temporarily suspended until further notice,” read a statement put out by the government on July 18. The Department of the Treasury (SHCP) has since stated that they expect the system to resume operations by the second week of August. Meanwhile, according to estimates made by think tank Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción (Mexicans Against Corruption), the government has made expenditures of as much as 60 billion pesos since the crash, based on average daily federal spending this year. “Opacity is the gateway for corruption. We know that government purchases are always sensitive and require maximum openness and maximum oversight,” notes University of Guadalajara professor and researcher Lourdes Morales. “With the platform offline, purchasing is happening as it did 30 years ago: in offices, with officials making decisions without any external supervision and probably without the presence of all eligible competitors,” according to an article in Animal Político.

The same week that CompraNet went offline, the PNT (National Transparency Platform) was the victim of 50 million cyberattacks or hacking attempts (from July 11-13). The attacks—caused by robotic fake submissions—were designed to cause a slowdown of the system and according to the INAI (National Institute for Transparency, Access to Information and Personal Data Protection) cybersecurity team, have been traced to foreign IP addresses.

It may come as a surprise—it did to me—that Mexico has a rigorous legal framework for public access to information. In fact, according to the Global Right to Information Rating, Mexico scores higher than the USA, Canada or the United Kingdom. Interestingly, so does India, which seems to signal that this ranking is detached from corruption indices, and that transparency can only go so far on its own.

The INAI was formed in 2002 and granted autonomy and ability to make legally binding resolutions in 2013. Prior to that, “getting data or a file to put together a story depended on the relationships reporters had with government sources…sometimes the scenes were surreal as public officials ‘leaked’ information that was delivered in suspicious packages…as if it was contraband,” explains journalist Sandra Romandía.

Today the INAI, through the PNT, provides a robust and moderately user-friendly system for reviewing public data and submitting requests. In comparison, the US FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) sites do seem outdated—“most federal agencies now accept FOIA requests electronically, including by web form, e-mail or fax”—and offer citizens response times of up to 280 working days. The INAI usually meets its legal obligation to respond to requests within 20 working days.

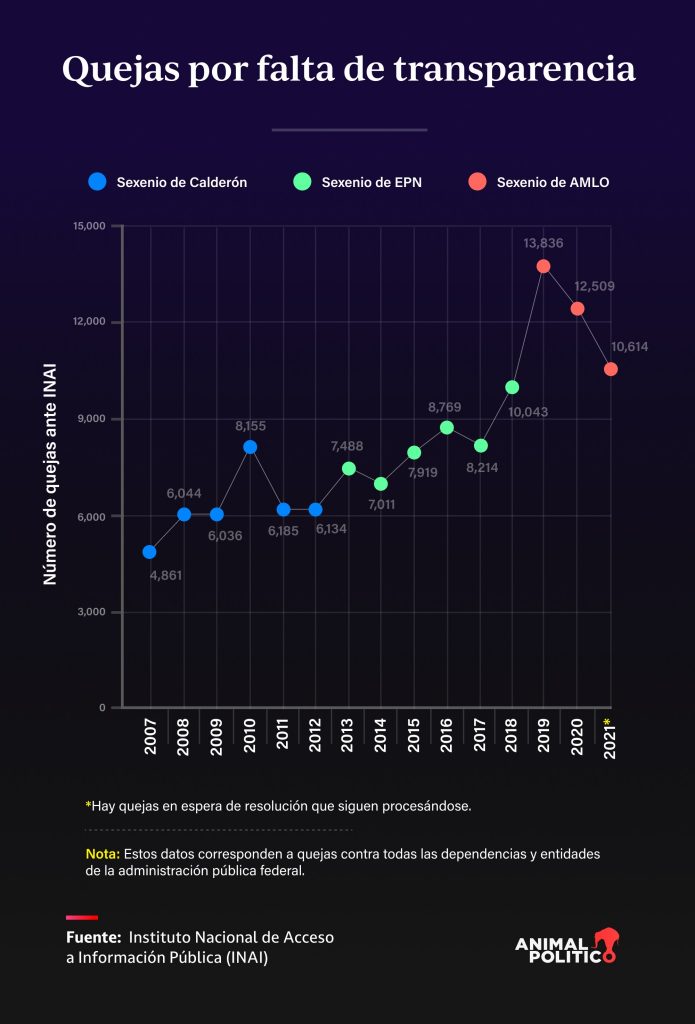

The agency hasn’t been exempt from controversy. In addition to providing access to public data, its mandate includes protecting individuals’ personal data and its use. There was a case in 2015 when the INAI ruled in favor of a magnate who had requested that Google remove three search results that contained negative information about his family’s business interests. Google appealed the ruling and won. Like many government institutions, the INAI has also come under attack from the current administration. In January 2019, President López Obrador proposed the dissolution of the agency and its absorption into the Secretaría de Funciones Públicas (Department of Public Services), which reports to the executive. AMLO and the INAI have been at odds ever since. This administration has had the highest annual registration of citizen complaints to INAI for lack of transparency in federal institutions. In November 2021, AMLO claimed the agency had been a costly sham for years, and that “now they (INAI) are very demanding, but we have nothing to hide, there is complete, utter transparency, because it is one of the golden rules of democracy. What would we have to hide? Nothing.”