By John Pint

In San Juan Evangelista, three generations have been developing their skills

There must be something special in the waters of Little Lake Cajititlán because every community around this lake located 25 kilometers south of Guadalajara seems to be brimming with artists and artisans.

Here you can find furniture utilizing woven reeds, sculptures made of basalt, works of art created from horsehair, magnificent ropes handmade from agave fibers and beautiful items produced from locally sourced clay.

It’s the artisans who make them that I want to talk about today.

They all happen to live in the pueblito of San Juan Evangelista, on the south side of the lake. Next to the town’s church, you’ll find a small Plaza de Los Artesanos (Artisans’ Plaza) surrounded by workshops where lumps of clay are turned into works of art.

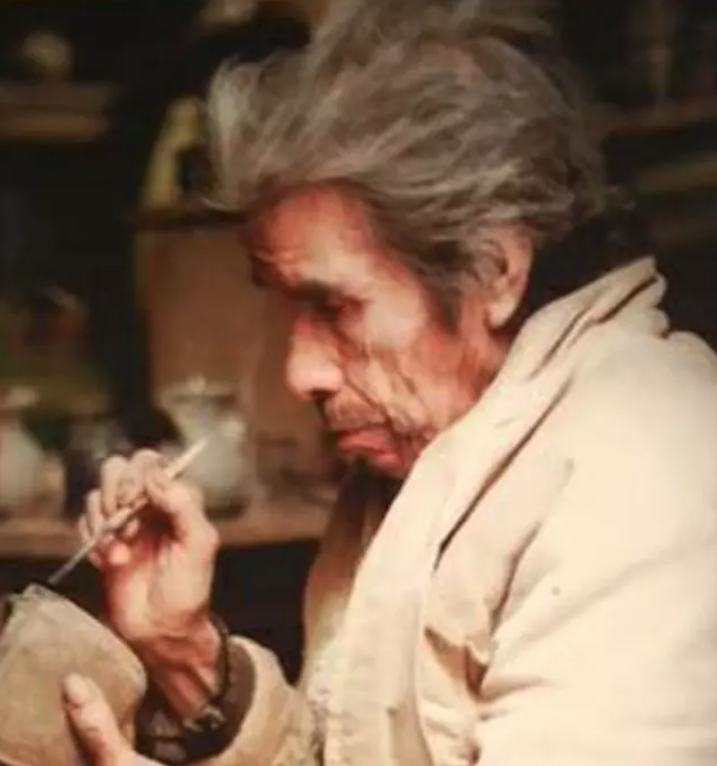

In 2012, the first time I visited the Artisans’ Plaza, I walked into the workshop of one Martín Navarro, who was intently working on a beautiful figure of an owl. Several other unfinished pieces lay on his desk, each one demonstrating this master sculptor’s extraordinary imagination, skill and attention to detail.

When we asked him about the ceramics tradition in San Juan, Navarro told us that three generations had been developing their skills in this medium, all of them inspired by his great uncle, Don Sixto Ibarra (1928–2001), who became interested in ceramics when he found figurines in a shaft tomb nearby.

“My great uncle started out trying to duplicate the ancient pieces he had discovered but ended up founding a school of creative sculpting, especially in the medium of barro bruñido, burnished clay.”

Burnishing, Navarro explained, involves rubbing chosen parts of the pot’s outside with a hard (usually metal) tool that rearranges and compresses the surface particles of clay, resulting in a smooth, even texture that almost looks like a glaze. I was amazed to learn that one of the artisans’ favorite tools for doing this is a stainless steel valve taken from a car engine.

Martín Navarro passed away a few years ago, but during his lifetime, he also inspired numerous neighbors to dedicate themselves to ceramics and pottery.

Two weeks ago, I revisited San Juan. This time, I walked into the workshop of Don Armando Barrera, who had learned pottery skills from his uncle — who had learned them at the knee of the celebrated Sixto Ibarra.

“I was 14 then,” Barrera told me, “but I was already producing my first pieces. Later I began to work independently. People would come along and ask me for something completely new. And me, I would never say no to them. ‘Claro que sí,’ I’d say. ‘Sure I can make that for you.’ I would say this even if I had no idea how to do it, and then I would have to put my mind to it, to actually make it happen. So I had to use my imagination.

For example, a local church asked him to make “clay paintings” showing Biblical scenes in circles one meter in diameter. “I had no idea you could paint with clay on a flat surface. But I learned to do it, and today my ceramic paintings are hanging right behind the altar of the church in [the town of] Cuexcomatitlán, at the west end of the lake.”

Similarly, Barrera had learned how to fire big, flat circles after teaching himself how to fire tabletops and chairs for clients who wanted ceramic furniture.

Over the years, he has worked out new techniques to achieve the effect of burnishing a pot since he sometimes has clients that want 100–200 pieces at a time.

“I add the shine after firing by applying water-based high-gloss sealer, the kind used for stone surfaces,” he said. “To get the same effect by burnishing with stainless steel or pyrite would take a day and a half for just one pot. But with this new technique, we can do 10 pots in the same amount of time. And on top of everything else, the sealer protects the piece in case it gets wet.”

I asked Barrera if he gets his clay from a place south of town that Navarro had shown me 10 years earlier.

“Yes, from the very same place,” he said. “I call this ‘virgin clay,’ and it’s what we use for really important things. It’s far better than anything I’ve ever seen anywhere else.”

What makes it so much better? “It’s not affected by humidity, and it’s not contaminated with lime, sand or volcanic rock like the clay they use in Guadalajara,” Barrera said. “It was Don Sixto Ibarra who found that deposit, but ‘mining’ it takes a lot of time and hard work.”

I can personally verify that last statement because when I visited the deposit in 2012, Navarro invited my wife and me to assist him in collecting a bit of that clay.

To get to the place, we walked for 2 kilometers along a dry mud track, our feet producing a loud crunching sound until we found ourselves in a silent wood. “There are still plenty of wild animals out here,” Navarro told us. “Right there, you can see coyote droppings, and we have mountain lions, deer, possum, badgers, rabbits … you name it.”

We soon arrived at a shady spot under the branches of a large tree. Just next to the shade tree was an embankment. Here, Navarro began to swing his pick, chipping away at the hard clay wall. I took my turn and soon we had produced a heap of thin, clay wedges.

“Now we have to break up the pieces,” he announced, “and the easiest way to do it is to dance on top of them.”

We enthusiastically took turns rhythmically stomping until no big clumps were left, at which point we began pulverizing the clay with a small sledgehammer. As we did this, Navarro told us about good and bad clay.

“What we have here is called barro canelo (cinnamon-color clay), and it’s ideal for pottery with good elasticity. My great uncle looked all over the place before he found this spot. Other kinds of clay were too sandy or had no consistency or would break after being baked.”

Having crushed the clay to the best of our ability, we sifted it through a fine mesh screen into a sturdy bag. The result was a very fine powder that Navarro said was perfect.

“At home, I will add water to a little of this powder to make a ball, and then I work it like dough, adding more and more powder until I get just the right consistency.”

That was in 2012. Today, Barrera told me, the artisans in the area have a serious problem: people want to build on that property.

“Once they do, we will never have access to our virgin clay again. And even if we did, the property could be resold over and over. Our local authorities are arguing that this is an archaeological site. Right now, we really need help to preserve this place!”

There are five families of potters in San Juan Evangelista, and they all seem to be named Ibarra, Navarro or Barrera, each of them with their own specialization. Some do pre-Hispanic-style dogs. Others make giant polychromatic jars. Of course, there are all kinds of vírgenes.

You’ll find most of these families around the Plaza de los Artesanos, but Don Armando’s place is at Calle Juárez 30. Since his workshop is also his home, you can visit just about any day of the week. Just give the family a call at 333 753 0104 or 331 066 4955 (WhatsApp).

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.

*This excerpt was published with authorization. To keep reading please search for the link to Mexico News Daily: https://mexiconewsdaily.com/mexicolife/in-this-town-families-turn-clay-into-art/